|

www.3-DLegends.com

Preserving stereoscopic

history of extraordinary people who have enriched our lives

|

| A Three Dimensional Life: Charles W. Smith FBKS FRPS 10 May 1920 - 13 May 2004 by Janet Leigh Foster |

The

road to 3-D appears in many guises, and Charles’ path was set to

music. Even though as a young adult Charles owned a stereo box camera,

his chief passion in life was not stereoscopy, but American jazz.

The

road to 3-D appears in many guises, and Charles’ path was set to

music. Even though as a young adult Charles owned a stereo box camera,

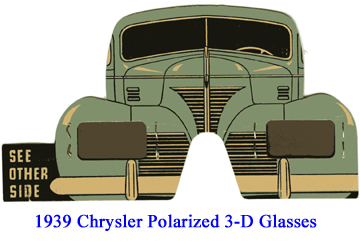

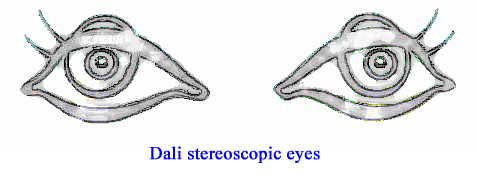

his chief passion in life was not stereoscopy, but American jazz.  One of the first 3-D films, “Motor Rhythm”,

made by John Norling for Chrysler Cars, was on offer, but the cinema in

which it was being shown was surrounded by a spiraling queue. Unaware

that in twenty years’ time he was to become a professional in the

field of stereoscopic cinema, Charles bypassed the opportunity and went

instead to Salvador Dali's’s Dream of Venus.

One of the first 3-D films, “Motor Rhythm”,

made by John Norling for Chrysler Cars, was on offer, but the cinema in

which it was being shown was surrounded by a spiraling queue. Unaware

that in twenty years’ time he was to become a professional in the

field of stereoscopic cinema, Charles bypassed the opportunity and went

instead to Salvador Dali's’s Dream of Venus.

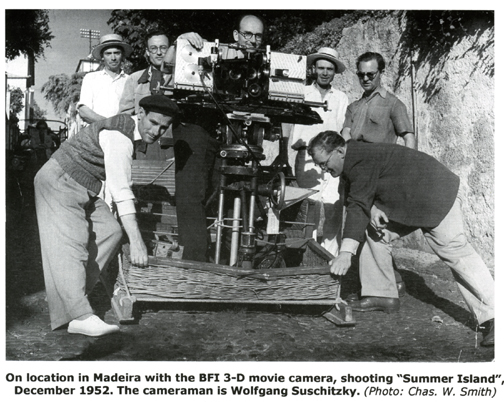

The

first three films from the festival had been made with the BFI 3-D

camera. Designed by Leslie Dudley, it was funded by the British Film

Institute (BFI). Like all prototypes, the BFI 3-D camera was less than

perfect. Its precision was rickety, and the film was constantly

shifting. The BFI 3-D camera was inadequate for Royal River,

so a new one was fabricated by mounting together two Technicolor

three-strip cameras. The apparatus was so heavy that six men were

needed to lift it. The BFI 3-D camera had to be completely rebuilt, and

it was at this point that Charles became involved with the project.

The

first three films from the festival had been made with the BFI 3-D

camera. Designed by Leslie Dudley, it was funded by the British Film

Institute (BFI). Like all prototypes, the BFI 3-D camera was less than

perfect. Its precision was rickety, and the film was constantly

shifting. The BFI 3-D camera was inadequate for Royal River,

so a new one was fabricated by mounting together two Technicolor

three-strip cameras. The apparatus was so heavy that six men were

needed to lift it. The BFI 3-D camera had to be completely rebuilt, and

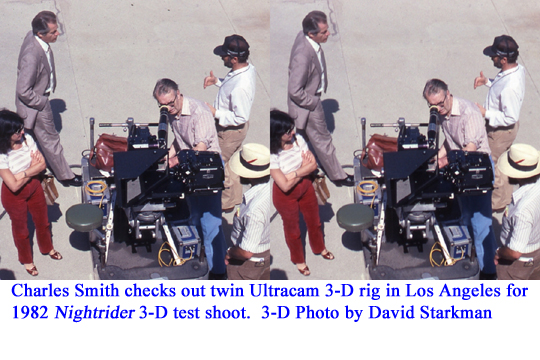

it was at this point that Charles became involved with the project.  easy to maneuver. It was decided to adapt a pair of French 35

millimeter Cameflexes, of high quality and lightweight, into a 3-D

movie camera. Making this in England was out of the question as no

English companies were doing that type of motion-picture engineering.

Hollywood was the best place. Charles was invited to go to Los Angeles

to act as a technical advisor.

easy to maneuver. It was decided to adapt a pair of French 35

millimeter Cameflexes, of high quality and lightweight, into a 3-D

movie camera. Making this in England was out of the question as no

English companies were doing that type of motion-picture engineering.

Hollywood was the best place. Charles was invited to go to Los Angeles

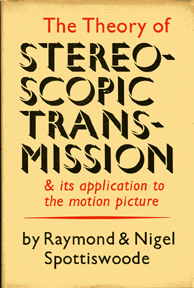

to act as a technical advisor. When

Charles arrived, Raymond Spottiswoode had already been there for about

two weeks, just long enough to be injured in a car accident.

Consequently, he had to shorten his stay. Spottiswoode limped around

and introduced Charles to the various people who were working on the

project, then left him there to finish it. In addition to the

camera, Charles’ duties came to include proof-reading the

technical information in The Theory of Stereoscopic Transmission and Its Application to the Motion Picture, a volume written by Raymond and Nigel Spottiswoode, published in Berkeley in 1953 by the University of California Press.

When

Charles arrived, Raymond Spottiswoode had already been there for about

two weeks, just long enough to be injured in a car accident.

Consequently, he had to shorten his stay. Spottiswoode limped around

and introduced Charles to the various people who were working on the

project, then left him there to finish it. In addition to the

camera, Charles’ duties came to include proof-reading the

technical information in The Theory of Stereoscopic Transmission and Its Application to the Motion Picture, a volume written by Raymond and Nigel Spottiswoode, published in Berkeley in 1953 by the University of California Press. As

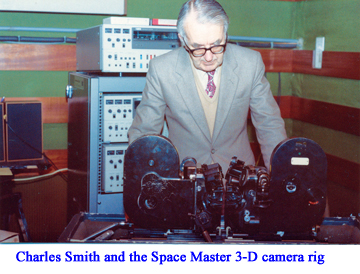

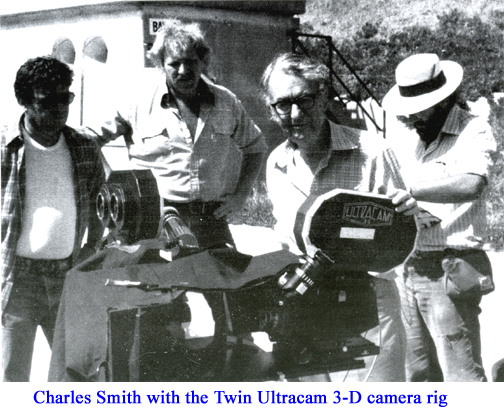

British stereoscopic cinema entered a dark age, Charles W. Smith

remained dedicated to tending its embers. He continued to earn a living

within the realm of two-dimensional cinematography, in what became the

best part of a thirty-year career at World Wide Pictures. His

responsibility to his family and his day job notwithstanding, Charles

was still compelled to heed the summons to 3-D when it arose.

As

British stereoscopic cinema entered a dark age, Charles W. Smith

remained dedicated to tending its embers. He continued to earn a living

within the realm of two-dimensional cinematography, in what became the

best part of a thirty-year career at World Wide Pictures. His

responsibility to his family and his day job notwithstanding, Charles

was still compelled to heed the summons to 3-D when it arose.

Charles

laments that during the fifty years since the Festival, there have been

few significant advances in 3-D cinematography. In Moscow in 1976 he

saw a thirty-second holographic film of a girl picking flowers, and in

1980 attended the 3-D film festival in Berlin. Nothing seemed to

suggest the advent of an era of distortion-free 3-D cinema with

comfortable viewing. Raymond Spottiswoode made great leaps in only

fourteen months. Charles believes that had the funding been available

to allow the field to develop, the results would have been

extraordinary.

Charles

laments that during the fifty years since the Festival, there have been

few significant advances in 3-D cinematography. In Moscow in 1976 he

saw a thirty-second holographic film of a girl picking flowers, and in

1980 attended the 3-D film festival in Berlin. Nothing seemed to

suggest the advent of an era of distortion-free 3-D cinema with

comfortable viewing. Raymond Spottiswoode made great leaps in only

fourteen months. Charles believes that had the funding been available

to allow the field to develop, the results would have been

extraordinary.

|

www.3-DLegends.com Preserving stereoscopic

history of extraordinary people who have enriched our lives

|

| HOME | David Hutchison | Seton Rochwite | Karl Struss | Paul Wing | Tommy Thomas | Arthur Girling | Tony Alderson | |